Jim Jones on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

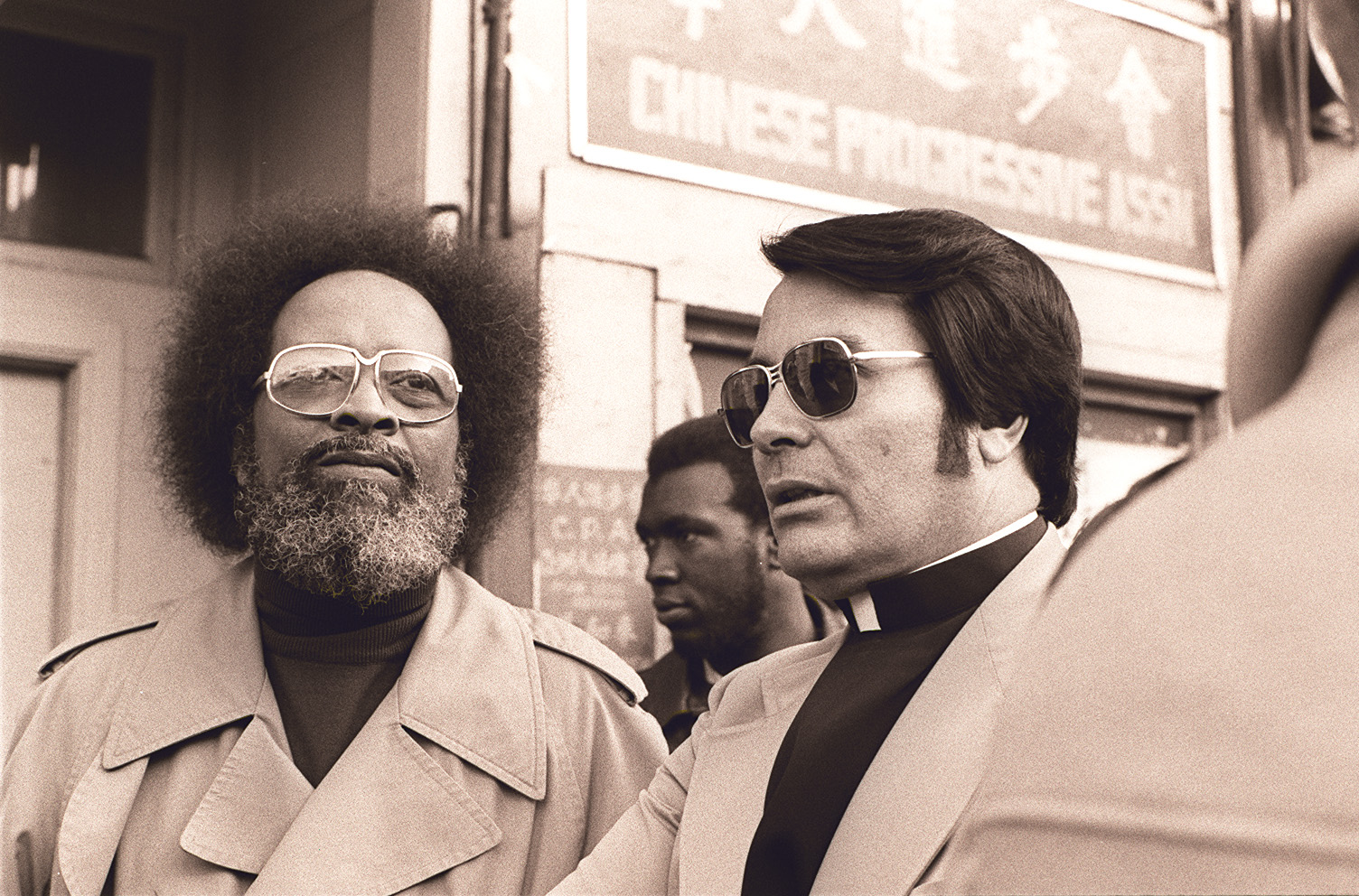

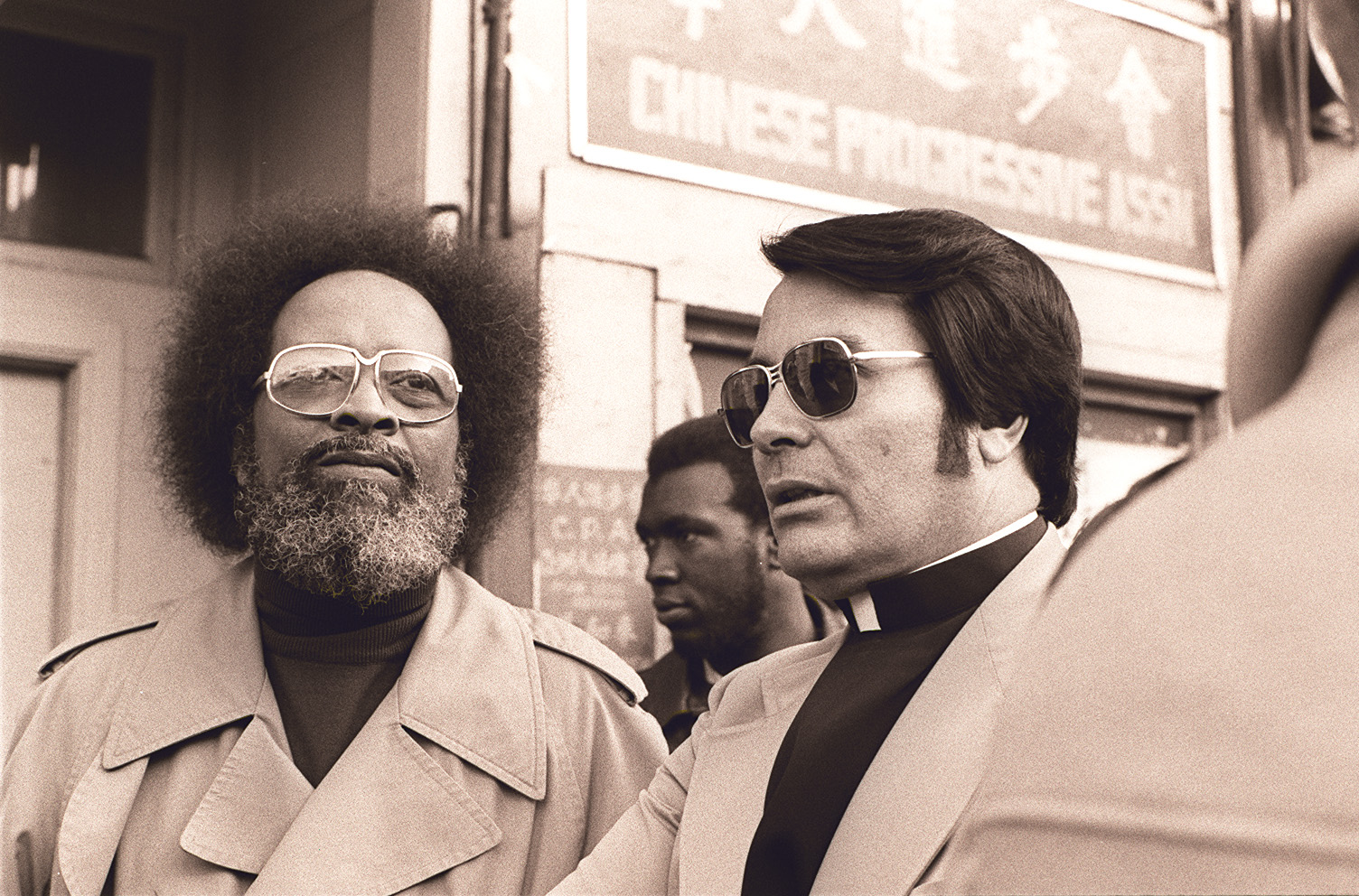

James Warren Jones (May 13, 1931 – November 18, 1978) was an American preacher, political activist and mass murderer. He led the

In early 1952, Jones announced to his wife and her family that he would become a Methodist minister, believing the church was ready to "put real socialism into practice." Jones was surprised when a

In early 1952, Jones announced to his wife and her family that he would become a Methodist minister, believing the church was ready to "put real socialism into practice." Jones was surprised when a  Believing that the racially integrated and rapidly growing Latter Rain movement offered him a greater opportunity to become a preacher, Jones successfully convinced his wife to leave the Methodist church and join the Pentecostals. In 1953, Jones began attending and preaching at the Laurel Street Tabernacle in Indianapolis, a Pentecostal

Believing that the racially integrated and rapidly growing Latter Rain movement offered him a greater opportunity to become a preacher, Jones successfully convinced his wife to leave the Methodist church and join the Pentecostals. In 1953, Jones began attending and preaching at the Laurel Street Tabernacle in Indianapolis, a Pentecostal

Branham was known to tell attendees their name, address, and why they came for prayer, before pronouncing them healed. Jones was intrigued by Branham's methods and began performing the same feats. Jones and Branham's meetings were very successful and attracted an audience of 11,000 at their first joint campaign. At the convention, Branham issued a prophetic endorsement of Jones and his ministry, saying that God used the convention to send forth a new great ministry.

Many attendees believed Jones's performance indicated that he possessed a supernatural gift, and coupled with Branham's endorsement, it led to rapid growth of Peoples Temple. Jones was particularly effective at recruitment among the African American attendees at the conventions. According to a newspaper report, regular attendance at Peoples Temple swelled to 1,000 thanks to the publicity Branham provided to Jones and Peoples Temple.

Following the convention, Jones renamed his church the "Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel" to associate it with

Branham was known to tell attendees their name, address, and why they came for prayer, before pronouncing them healed. Jones was intrigued by Branham's methods and began performing the same feats. Jones and Branham's meetings were very successful and attracted an audience of 11,000 at their first joint campaign. At the convention, Branham issued a prophetic endorsement of Jones and his ministry, saying that God used the convention to send forth a new great ministry.

Many attendees believed Jones's performance indicated that he possessed a supernatural gift, and coupled with Branham's endorsement, it led to rapid growth of Peoples Temple. Jones was particularly effective at recruitment among the African American attendees at the conventions. According to a newspaper report, regular attendance at Peoples Temple swelled to 1,000 thanks to the publicity Branham provided to Jones and Peoples Temple.

Following the convention, Jones renamed his church the "Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel" to associate it with

Through the Latter Rain movement, Jones became aware of

Through the Latter Rain movement, Jones became aware of

In 1960, Indianapolis Mayor Charles Boswell appointed Jones director of the local

In 1960, Indianapolis Mayor Charles Boswell appointed Jones director of the local

Among the followers Jones took to Guyana was John Victor Stoen. John's birth certificate listed

Among the followers Jones took to Guyana was John Victor Stoen. John's birth certificate listed

In November 1978, Congressman Ryan led a

In November 1978, Congressman Ryan led a

Later the same day, November 18, 1978, Jones received word that his security guards failed to kill all of Ryan's party. Jones concluded the escapees would soon inform the United States of the attack and they would send the military to seize Jonestown. Jones called the entire community to the central pavilion. He informed the community that Ryan was dead and it was only a matter of time before military commandos descended on their commune and killed them all.

Jones told Temple members that the Soviet Union would not give them passage after the airstrip shooting. Jones said "We can check with Russia to see if they’ll take us in immediately, otherwise we die," asking, "You think Russia’s gonna want us with all this stigma?"

With that reasoning, Jones and several members argued that the group should commit "revolutionary suicide". Jones recorded the entire death ritual on audio tape. Jones had taken large shipments of

Later the same day, November 18, 1978, Jones received word that his security guards failed to kill all of Ryan's party. Jones concluded the escapees would soon inform the United States of the attack and they would send the military to seize Jonestown. Jones called the entire community to the central pavilion. He informed the community that Ryan was dead and it was only a matter of time before military commandos descended on their commune and killed them all.

Jones told Temple members that the Soviet Union would not give them passage after the airstrip shooting. Jones said "We can check with Russia to see if they’ll take us in immediately, otherwise we die," asking, "You think Russia’s gonna want us with all this stigma?"

With that reasoning, Jones and several members argued that the group should commit "revolutionary suicide". Jones recorded the entire death ritual on audio tape. Jones had taken large shipments of

The Jonestown Institute

*

Jim Jones

. ''

Jonestown 30 Years Later

photo gallery published Friday, October 17, 2008.

Jonestown

-

Peoples Temple

The Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ, originally Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church and commonly shortened to Peoples Temple, was an American new religious organization which existed between 1954 and 1978. Founded in Indianapolis, Ind ...

, a new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as alternative spirituality or a new religion, is a religious or spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or th ...

, between 1955 and 1978. In what he called "revolutionary suicide", Jones and the members of his inner circle orchestrated a mass murder–suicide in his remote jungle commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

at Jonestown

The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, better known by its informal name "Jonestown", was a remote settlement in Guyana established by the Peoples Temple, a U.S.–based cult under the leadership of Jim Jones. Jonestown became internationall ...

, Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

, on November 18, 1978. Jones and the events which occurred at Jonestown have had a defining influence on society's perception of cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This ...

s.

As a child, Jones developed an affinity for Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement

and a desire to preach. He was ordained as a Christian minister in the Independent Assemblies of God

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independen ...

, attracting his first group of followers while participating in the Pentecostal Latter Rain movement and the Healing Revival during the 1950s. Jones's initial popularity arose from his joint campaign appearances with the movements' prominent leaders, William Branham

William Marrion Branham (April 6, 1909 – December 24, 1965) was an American Christian minister and faith healer who initiated the post-World War II healing revival, and claimed to be a prophet with the anointing of Elijah, who had come t ...

and Joseph Mattsson-Boze

Joseph D. Mattsson-Boze (died January 1989) was a Swedish-American minister and pastor of Chicago's Philadelphia Church from 1933 to 1958, with the exception of 1939-1941 when he pastored the Rock Church in New York. He was publisher and editor ...

, and their endorsement of his ministry. Jones founded the organization that would become the Peoples Temple in Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

in 1955. In 1956, Jones began to be influenced by Father Divine

Father Divine (September 10, 1965), also known as Reverend M. J. Divine, was an African-American spiritual leader from about 1907 until his death in 1965. His full self-given name was Reverend Major Jealous Divine, and he was also known as "t ...

and the Peace Mission movement. Jones distinguished himself through civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

activism, founding the Temple as a fully integrated congregation, and promoting socialism. In 1964, Jones joined and was ordained a minister by the Disciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

; his attraction to the Disciples was largely due to the autonomy and tolerance they granted to differing views within their denomination.

In 1965, Jones moved the Temple to California. The group established its headquarters in San Francisco, where he became heavily involved in political and charitable activity throughout the 1970s. Jones developed connections with prominent California politicians and was appointed as chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission in 1975. Beginning in the late 1960s, reports of abuse began to surface as Jones became increasingly vocal in his rejection of traditional Christianity and began promoting a form of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

he called "Apostolic Socialism" and making claims of his own divinity. Jones became progressively more controlling of his followers in Peoples Temple, which at its peak had over 3,000 members. Jones's followers engaged in a communal lifestyle in which many turned over all their income and property to Jones and Peoples Temple who directed all aspects of community life.

Following a period of negative media publicity and reports of abuse at Peoples Temple, Jones ordered the construction of the Jonestown commune in Guyana in 1974 and convinced or compelled many of his followers to live there with him. Jones claimed that he was constructing a socialist paradise free from the oppression of the United States government. By 1978, reports surfaced of human rights abuses and accusations that people were being held in Jonestown against their will. U.S. Representative Leo Ryan

Leo Joseph Ryan Jr. (May 5, 1925 – November 18, 1978) was an American teacher and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the U.S. representative from California's 11th congressional district from 1973 until his assassina ...

led a delegation to the commune in November of that year to investigate these reports. While boarding a return flight with some former Temple members who wished to leave, Ryan and four others were murdered by gunmen from Jonestown. Jones then ordered a mass murder-suicide that claimed the lives of 909 commune members, 304 of them children; almost all of the members died by drinking Flavor Aid

Flavor Aid is a non-carbonated soft drink beverage made by The Jel Sert Company in West Chicago, Illinois. It was introduced in 1929. It is sold throughout the United States as an unsweetened, powdered concentrate drink mix, similar to Kool-Ai ...

laced with cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

.

Early life

James Warren Jones was born on May 13, 1931, in the rural community ofCrete, Indiana

Crete is a small unincorporated community in Greensfork Township, Randolph County, in the U.S. state of Indiana.

History

A post office was established at Crete in 1882, and remained in operation until it was discontinued in 1918. The community ma ...

, to James Thurman Jones and Lynetta Putnam. Jones's father was a disabled World WarI veteran who suffered from severe breathing difficulties due to injuries which he sustained in a chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized Ammunition, munition that uses chemicals chemical engineering, formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be an ...

attack.

His father's illness led to financial difficulties. In 1934, the Jones family was evicted from their home for failure to make mortgage payments. Their relatives purchased a shack for them to live in at the nearby town of Lynn. The new home, where Jones grew up, lacked plumbing and electricity. In Lynn, the family attempted to earn an income through farming, but again met with failure when Jones's father's health further deteriorated. The family often lacked adequate food and relied on financial support from their extended family. They sometimes resorted to foraging in the nearby forest and fields to supplement their diet.

According to multiple Jones biographers, his mother had "no natural maternal instincts" and as a result, she frequently neglected her son. When Jones started to attend school, his extended family threatened to cut off their financial assistance unless his mother got a job, forcing her to work outside her home. Meanwhile, Jones's father was hospitalized multiple times due to his illness. As a result, Jones's parents were frequently absent during his childhood. Jones was left to be cared for by neighbors and relatives.

Early religious and political influences

Myrtle Kennedy, the wife of theNazarene Church

The Church of the Nazarene is an evangelical Christian denomination that emerged in North America from the 19th-century Wesleyan-Holiness movement within Methodism. It is headquartered in Lenexa within Johnson County, Kansas. With its members c ...

's pastor, developed a special attachment to Jones. She gave Jones a Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

and encouraged him to study it, teaching him to follow the holiness code

The Holiness code is used in biblical criticism to refer to Leviticus chapters 17–26, and sometimes passages in other books of the Pentateuch, especially Numbers and Exodus. It is so called due to its highly repeated use of the word ''holy ...

of the Nazarene Church. As Jones grew older, he attended services at most of the churches in Lynn, often going to multiple churches each week, and he was baptized in several of them. Jones developed a desire to become a preacher as a child and he began to practice preaching in private. His mother claimed that she was disturbed when she caught him imitating the pastor of the local Apostolic Pentecostal Church and she unsuccessfully attempted to prevent him from attending the church's services.

Although they had sympathy for Jones because of his poor circumstances, his neighbors reported that he was an unusual child who was obsessed with religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

and death. One Jones biographer suggested that he developed his unusual interests because he found it difficult to make friends. Although his strange religious practices stood out the most to his neighbors, they reported that he misbehaved in more serious ways. He frequently stole candy from merchants in the town; his mother was required to pay for his thefts. Jones regularly used offensive profanity

Profanity, also known as cursing, cussing, swearing, bad language, foul language, obscenities, expletives or vulgarism, is a socially offensive use of language. Accordingly, profanity is language use that is sometimes deemed impolite, rud ...

, commonly greeting his friends and neighbors by saying, "Good morning, you son of a bitch" or, "Hello, you dirty bastard".

Jones developed an intense interest in religion and social doctrines. He became a voracious reader who studied Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

and Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

. He spent hours in the community library, and he brought books home so he could read them in the evenings. Although he studied different political systems, Jones did not espouse any radical political views in his youth.

Commenting on his childhood, Jones stated, Tim Reiterman, a biographer of Jones, wrote that Jones's attraction to religion was strongly influenced by his desire for a family.

Education and marriage

In high school, Jones continued to stand out from his peers. He almost always carried his Bible with him. His religious views alienated him from other young people. He frequently confronted them for drinking beer, smoking, and dancing. While he was attending a baseball game inRichmond, Indiana

Richmond is a city in eastern Wayne County, Indiana. Bordering the state of Ohio, it is the county seat of Wayne County and is part of the Dayton, OH Metropolitan Statistical Area In the 2010 census, the city had a population of 36,812. Situa ...

, Jones was bothered by the treatment of African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

who attended the game. The events at that baseball game brought discrimination against African Americans to Jones's attention and influenced his strong aversion to racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

.

Jones's parents separated in 1945 and they eventually divorced. Jones moved to Richmond, Indiana with his mother, where he graduated from Richmond High School in December 1948. Jones and his mother lost the financial support of their relatives following the divorce. To support himself, Jones began working as an orderly at Richmond's Reid Hospital in 1946. Jones was well-regarded by the senior management, but staff members later recalled that Jones exhibited disturbing behavior towards some patients and coworkers. Jones began dating a nurse-in-training named Marceline Baldwin while he was working at Reid Hospital.

Jones moved to Bloomington, Indiana

Bloomington is a city in and the county seat of Monroe County, Indiana, Monroe County in the central region of the U.S. state of Indiana. It is the List of municipalities in Indiana, seventh-largest city in Indiana and the fourth-largest outside ...

in November 1948, where he attended Indiana University Bloomington

Indiana University Bloomington (IU Bloomington, Indiana University, IU, or simply Indiana) is a public university, public research university in Bloomington, Indiana. It is the flagship university, flagship campus of Indiana University and, with ...

with the intention of becoming a doctor, but changed his mind shortly thereafter. During his time at University, Jones was impressed by a speech which Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

delivered about the plight of African-Americans, and he began to espouse support for communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and other radical political views for the first time.

Jones and Marceline Baldwin continued their relationship while he attended college, and the couple married on June 12, 1949. Their first home was in Bloomington, where Marceline worked in a nearby hospital while Jones attended college. Marceline was Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

, and she and Jones immediately fell into arguments about church. Jones's strong opposition to the Methodist church's racial segregationist practices was an early strain on their marriage. Jones insisted on attending Bloomington's Full Gospel Tabernacle, but eventually compromised and began attending a local Methodist church on most Sunday mornings. Despite attending churches every week, Jones privately pressed his wife to accept atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

.

After attending Indiana University for two years, the couple relocated to Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

in 1951. Jones took night classes at Butler University

Butler University is a private university in Indianapolis, Indiana. Founded in 1855 and named after founder Ovid Butler, the university has over 60 major academic fields of study in six colleges: the Lacy School of Business, College of Communic ...

to continue his education, finally earning a degree in secondary education in 1961.

In 1951, the 20-year-old Jones began attending gatherings of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

in Indianapolis. Jones and his family faced harassment from government authorities for their affiliation with the Communist Party during 1952. In one event, Jones's mother was harassed by FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

agents in front of her co-workers because she had attended a communist meeting with her son.. Jones became frustrated with the persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

of communists in the U.S. Reflecting back on his participation in the Communist Party, Jones said that he asked himself, "How can I demonstrate my Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

? The thought was, infiltrate the church."

Peoples Temple

Beginnings in Indianapolis

In early 1952, Jones announced to his wife and her family that he would become a Methodist minister, believing the church was ready to "put real socialism into practice." Jones was surprised when a

In early 1952, Jones announced to his wife and her family that he would become a Methodist minister, believing the church was ready to "put real socialism into practice." Jones was surprised when a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

district superintendent helped him get a start in the church, even though he knew Jones to be a communist.

In the summer of 1952, Jones was hired as student pastor to the children at the Sommerset Southside Methodist Church, where he launched a project to create a playground that would be open to children of all races. Jones continued to visit and speak at Pentecostal churches while serving as Methodist student pastor. In early 1954 Jones was dismissed from his position in the Methodist Church, ostensibly for stealing church funds, though he later claimed he left the church because its leaders forbade him from integrating blacks into his congregation.

Around this time in 1953, Jones visited a Pentecostal Latter Rain convention in Columbus, Indiana

Columbus is a city in and the county seat of Bartholomew County, Indiana, United States. The population was 50,474 at the 2020 census. The relatively small city has provided a unique place for noted Modern architecture and public art, commissio ...

, where a woman prophesied that Jones was a prophet with a great ministry. Jones was surprised by the endorsement, but gladly accepted the call to preach and rose to the podium to deliver a message to the crowd. Pentecostalism was in the midst of the Healing Revival and Latter Rain movements during the 1950s.

Assemblies of God

The Assemblies of God (AG), officially the World Assemblies of God Fellowship, is a group of over 144 autonomous self-governing national groupings of churches that together form the world's largest Pentecostal denomination."Assemblies of God". ...

church. Jones held healing revivals there until 1955 and began to travel and speak at other churches in the Latter Rain movement. He was a guest speaker at a 1953 convention in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

.

The Assemblies of God was strongly opposed to the Latter Rain movement. In 1955, they assigned a new pastor to the Laurel Street Tabernacle who enforced their denominational ban on healing revivals. This led Jones to leave and establish Wings of Healing, a new church that would later be renamed Peoples Temple. Jones's new church attracted only twenty members who had come with him from the Laurel Street Tabernacle and was not able to financially support his vision. Jones saw a need for publicity, and began seeking a way to popularize his ministry and recruit members.

Latter Rain movement

Jones began to closely associate with theIndependent Assemblies of God

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independen ...

(IAoG), an international group of churches which embraced the Latter Rain movement. The IAoG had few requirements for ordaining ministers and they were also accepting of divine healing practices. In June 1955, Jones held his first joint meetings with William Branham

William Marrion Branham (April 6, 1909 – December 24, 1965) was an American Christian minister and faith healer who initiated the post-World War II healing revival, and claimed to be a prophet with the anointing of Elijah, who had come t ...

, a healing evangelist

Evangelist may refer to:

Religion

* Four Evangelists, the authors of the canonical Christian Gospels

* Evangelism, publicly preaching the Gospel with the intention of spreading the teachings of Jesus Christ

* Evangelist (Anglican Church), a c ...

and Pentecostal leader in the global Healing Revival.

In 1956, Jones was ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

as an IAoG minister by Joseph Mattsson-Boze

Joseph D. Mattsson-Boze (died January 1989) was a Swedish-American minister and pastor of Chicago's Philadelphia Church from 1933 to 1958, with the exception of 1939-1941 when he pastored the Rock Church in New York. He was publisher and editor ...

, a leader in the Latter Rain movement and the IAoG. Jones quickly rose to prominence in the group and organized and hosted a healing convention to take place June 11–15, 1956, in Indianapolis's Cadle Tabernacle. Needing a well-known figure to draw crowds, he arranged to share the pulpit again with Branham.

Branham was known to tell attendees their name, address, and why they came for prayer, before pronouncing them healed. Jones was intrigued by Branham's methods and began performing the same feats. Jones and Branham's meetings were very successful and attracted an audience of 11,000 at their first joint campaign. At the convention, Branham issued a prophetic endorsement of Jones and his ministry, saying that God used the convention to send forth a new great ministry.

Many attendees believed Jones's performance indicated that he possessed a supernatural gift, and coupled with Branham's endorsement, it led to rapid growth of Peoples Temple. Jones was particularly effective at recruitment among the African American attendees at the conventions. According to a newspaper report, regular attendance at Peoples Temple swelled to 1,000 thanks to the publicity Branham provided to Jones and Peoples Temple.

Following the convention, Jones renamed his church the "Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel" to associate it with

Branham was known to tell attendees their name, address, and why they came for prayer, before pronouncing them healed. Jones was intrigued by Branham's methods and began performing the same feats. Jones and Branham's meetings were very successful and attracted an audience of 11,000 at their first joint campaign. At the convention, Branham issued a prophetic endorsement of Jones and his ministry, saying that God used the convention to send forth a new great ministry.

Many attendees believed Jones's performance indicated that he possessed a supernatural gift, and coupled with Branham's endorsement, it led to rapid growth of Peoples Temple. Jones was particularly effective at recruitment among the African American attendees at the conventions. According to a newspaper report, regular attendance at Peoples Temple swelled to 1,000 thanks to the publicity Branham provided to Jones and Peoples Temple.

Following the convention, Jones renamed his church the "Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel" to associate it with Full Gospel The term Full Gospel or Fourfold Gospel is a theological doctrine used by some evangelical denominations that summarizes the Gospel in four aspects, namely salvation, sanctification, divine healing and second coming of Christ.

Doctrine

This term ...

Pentecostalism; the name was later shortened to the Peoples Temple. Jones participated in a series of multi-state revival campaigns with Branham in the second half of the 1950s. Jones claimed to be a follower and promoter of Branham's "Message" during the period. Peoples Temple hosted a second international Pentecostal convention in 1957 which was again headlined by Branham. Through the conventions and with the support of Branham and Mattsson-Boze, Jones secured connections throughout the Latter Rain movement.

Jones adopted one of the Latter Rain's key doctrines which he continued to promote for the rest of his life: the Manifested Sons of God. William Branham and the Latter Rain movement promoted the belief that individuals could become manifestations of God with supernatural gifts and superhuman abilities. They believed that such a manifestation signaled the second coming of Christ

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

, and that the people endowed with these special gifts would usher in a millennial age of heaven on earth. Jones was fascinated with the idea, and adapted it to promote his own utopian ideas and eventually the idea that he was himself a manifestation of God. By the late 1960s, Jones came to teach he was a manifestation of "Christ the Revolution".

Branham was a major influence on Jones who subsequently adopted elements of Branham's methods, doctrines, and style. Like Branham, Jones would later claim to be a return of Elijah the Prophet

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books o ...

, the voice of God, a manifestation of Christ, and promote the belief that the end of the world was imminent. Jones learned some of his most successful recruitment tactics from Branham. Jones eventually separated from the Latter Rain movement following a bitter disagreement with Branham in which Jones prophesied Branham's death. Their disagreement was possibly related to Branham's racial teachings or Branham's increasingly vocal opposition to communism.

Peace Mission Movement

Through the Latter Rain movement, Jones became aware of

Through the Latter Rain movement, Jones became aware of Father Divine

Father Divine (September 10, 1965), also known as Reverend M. J. Divine, was an African-American spiritual leader from about 1907 until his death in 1965. His full self-given name was Reverend Major Jealous Divine, and he was also known as "t ...

, an African American spiritual leader of the International Peace Mission movement who was often derided by Pentecostal ministers for his claims to divinity. In 1956, Jones made his first visit to investigate Father Divine

Father Divine (September 10, 1965), also known as Reverend M. J. Divine, was an African-American spiritual leader from about 1907 until his death in 1965. His full self-given name was Reverend Major Jealous Divine, and he was also known as "t ...

's Peace Mission in Philadelphia. Jones was careful to explain that his visit to the Peace Mission was so he could "give an authentic, unbiased, and objective statement" about its activities to his fellow Pentecostal ministers.

Divine served as another important influence on the development of Jones's ministry. While publicly disavowing many of Father Divine's teachings, Jones actually began to promote Divine's teachings on communal living and gradually implemented many of the outreach practices he witnessed at the Peace Mission, including setting up a soup kitchen and providing free groceries and clothing to people in need.

Jones made a second visit to Father Divine in 1958 to learn more about his practices. Jones bragged to his congregation that he would like to be the successor of Father Divine and made many comparisons between their two ministries. Jones began progressively implementing the disciplinary practices he learned from Father Divine which increasingly took control over the lives of members of Peoples Temple.

Disciples of Christ

As Jones gradually separated from Pentecostalism and the Latter Rain movement, he sought an organization that would be open to all of his beliefs. In 1960, Peoples Temple joined theDisciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

denomination, whose headquarters was nearby in Indianapolis. Archie Ijames assured Jones that the organization would tolerate his political beliefs, and Jones was finally ordained by Disciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

in 1964.

Jones was ordained as a Disciples minister at a time when the requirements for ordination varied greatly and Disciples membership was open to any church. In both 1974 and 1977 the Disciples leadership received allegations of abuse at Peoples Temple. They conducted investigations at the time, but they found no evidence of wrongdoing. Disciples of Christ found Peoples Temple to be "an exemplary Christian ministry overcoming human differences and dedicated to human services." Peoples Temple contributed $1.1 million ($ in 2020 dollars) to the denomination between 1966 and 1977. Jones and Peoples Temple remained part of the Disciples until the Jonestown massacre.

Racial integration

In 1960, Indianapolis Mayor Charles Boswell appointed Jones director of the local

In 1960, Indianapolis Mayor Charles Boswell appointed Jones director of the local human rights commission

A human rights commission, also known as a human relations commission, is a body set up to investigate, promote or protect human rights.

The term may refer to international, national or subnational bodies set up for this purpose, such as nationa ...

. Jones ignored Boswell's advice to keep a low profile, however, and he used the position to secure new outlets for his views on local radio and television programs. The mayor and other commissioners asked him to curtail his public actions, but he refused. Jones was wildly cheered at a meeting of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

and the Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

when he encouraged his audience to be more militant

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin " ...

, capping his speech with, "Let my people go!".

During his time as commission director, Jones helped to racially integrate churches, restaurants, the telephone company, the Indianapolis Police Department

The Indianapolis Police Department (IPD) (September 1, 1854 – December 31, 2006) was the principal law enforcement agency of Indianapolis, Indiana, under the jurisdiction of the Mayor of Indianapolis and Director of Public Safety. Prior to ...

, a theater, and an amusement park, and the Indiana University Health Methodist Hospital

Indiana University Health Methodist Hospital is a hospital part of Indiana University Health, located in Indianapolis, state of Indiana, United States. It is the largest hospital in the state of Indiana and one of only four regional Level I Traum ...

. When swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

s were painted on the homes of two black families, Jones walked through the neighborhood, comforted the local black community and counseled white families not to move.

Jones set up sting operation

In law enforcement, a sting operation is a deceptive operation designed to catch a person attempting to commit a crime. A typical sting will have an undercover law enforcement officer, detective, or co-operative member of the public play a role a ...

s in order to catch restaurants which refused to serve black customers and wrote to American Nazi Party

The American Nazi Party (ANP) is an American far-right and neo-Nazi political party founded by George Lincoln Rockwell and headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. The organization was originally named the World Union of Free Enterprise National ...

leaders and passed their responses to the media. In 1961, Jones suffered a collapse and was hospitalized. The hospital accidentally placed Jones in its black ward, and he refused to be moved; he began to make the beds and empty the bedpan

A bedpan or bed pan is a receptacle used for the toileting of a bedridden patient in a health care facility, and is usually made of metal, glass, ceramic, or plastic. A bedpan can be used for both urinary and fecal discharge. Many diseases can ...

s of black patients. Political pressures which resulted from Jones's actions caused hospital officials to desegregate

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

the wards.

In Indiana, Jones was criticized for his integrationist views. Peoples Temple became a target of white supremacists. Among several incidents, a swastika was placed on the Temple, a stick of dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and Stabilizer (chemistry), stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish people, Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germa ...

was left in a Temple coal pile, and a dead cat was thrown at Jones's house after a threatening phone call. Nevertheless, the publicity which was generated by Jones's activities attracted a larger congregation. By the end of 1961, Indianapolis was a far more racially integrated city, and "Jim Jones was almost entirely responsible."

"Rainbow Family"

Jones and his wife adopted several non-white children. Jones referred to his household as a "rainbow family", and stated: "Integration is a more personal thing with me now. It's a question of my son's future." He also portrayed the Temple as a "rainbow family". In 1954 the Joneses adopted their first child, Agnes, who was part Native American. In 1959, they adopted three Korean-American children named Lew, Stephanie, and Suzanne, and encouraged Temple members to adopt orphans from war-ravaged Korea. Stephanie Jones died at age five in a car accident in May 1959. In June 1959, Jones and his wife had their only biological child, naming him Stephan Gandhi. In 1961, they became the first white couple in Indiana to adopt a black child, naming him Jim Jones Jr. (or James W. Jones Jr.). They adopted a white son, originally named Timothy Glen Tupper (shortened to Tim), whose birth mother was a member of the Temple. Jones fathered Jim Jon (Kimo) with Temple member Carolyn Layton.Relocating Peoples Temple

In 1961, Jones warned his congregation that he had received visions of a nuclear attack that would devastate Indianapolis. His wife confided to her friends that he was becoming increasingly paranoid and fearful. Like other followers of William Branham who moved to South America during the 1960s, Jones may have been influenced by Branham's 1961 prophecy concerning the destruction of the United States in a nuclear war. Jones began to look for a way to escape the destruction he believed was imminent. In January 1962 he read an ''Esquire

Esquire (, ; abbreviated Esq.) is usually a courtesy title.

In the United Kingdom, ''esquire'' historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentlema ...

'' magazine article that purported South America to be the safest place to reside to escape any impending nuclear war. Jones decided to travel to South America to scout for a site to relocate Peoples Temple.

Jones made a stop in Georgetown, Guyana on his way to Brazil. Jones held revival meetings in Guyana, which was an english-speaking British colony

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remnants of the former Bri ...

. Continuing to Brazil, Jones's family rented a modest three-bedroom home in Belo Horizonte

Belo Horizonte (, ; ) is the sixth-largest city in Brazil, with a population around 2.7 million and with a metropolitan area of 6 million people. It is the 13th-largest city in South America and the 18th-largest in the Americas. The metropol ...

. Jones studied the local economy and receptiveness of racial minorities to his message, but found language to be a barrier. Careful not to portray himself as a communist, he spoke of an apostolic communal lifestyle rather than Marxism. The family moved to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

in mid-1963, where they worked with the poor in the ''favela

Favela () is an umbrella name for several types of working-class neighborhoods in Brazil. The term was first used in the Providência neighborhood in the center of Rio de Janeiro in the late 19th century, which was built by soldiers who had ...

s''.

Unable to find a location he deemed suitable for Peoples Temple, Jones became plagued by guilt for abandoning the civil rights struggle in Indiana. During the year of his absence, regular attendance at Peoples Temple declined to less than 100. Jones demanded the Peoples Temple send all its revenue to him in South America to support his efforts and the church went into debt to support his mission. In late 1963, Archie Ijames sent word that the Temple was about to collapse, and threatened to resign if Jones did not soon return. Jones reluctantly returned to Indiana.

Jones arrived in December 1963 to find Peoples Temple bitterly divided. Financial issues and low attendance forced Jones to sell the Peoples Temple church building and relocate to a smaller building nearby. To raise money, Jones briefly returned to the revival circuit, traveling and holding healing campaigns with Latter Rain groups. Possibly to distract Peoples Temple members from the issues facing their group, he told his Indiana congregation that the world would be engulfed by nuclear war on July 15, 1967, leading to a new socialist Eden on Earth, and that the Temple must move to Northern California

Northern California (colloquially known as NorCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. Spanning the state's northernmost 48 counties, its main population centers incl ...

for safety.

During 1964, Jones made multiple trips to California to find a suitable location to relocate. In July 1965, Jones and his followers began moving to their new location in Redwood Valley, California

Redwood Valley (formerly Basil) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Mendocino County, California, United States. It is located north of Ukiah, the county seat, at an elevation of , and comprises the northern portion of the Ukiah Valley. It i ...

, near the city of Ukiah. Russell Winberg, Peoples Temple's assistant pastor, strongly resisted Jones's efforts to move the congregation and warned members that Jones was abandoning Christianity. Winberg took over leadership of the Indianapolis church when Jones departed. About 140 of Jones's most loyal followers made the move to California, while the rest remained behind with Winberg.

In California, Jones took a job as a history and government teacher at an adult education school in Ukiah. Jones used his position to recruit for Peoples Temple, teaching his students the benefits of Marxism and lecturing on religion. Jones planted loyal members of Peoples Temple in the classes to help him with recruitment. Jones recruited 50 new members to Peoples Temple in the first few months. In 1967, Jones's followers coaxed another 75 members of the Indianapolis congregation to move to California.

In 1968, the Peoples Temple's California location was admitted to the Disciples of Christ. Jones began to use the denominational connection to promote Peoples Temple as part of the 1.5 million member denomination. He played up famous members of the Disciples, including Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

and J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

, and misrepresented the nature of his position in the denomination. By 1969, Jones increased the membership in Peoples Temple in California to 300.

Apostolic Socialism

Jones developed a theology influenced by the teachings of William Branham and the Latter Rain movement, Father Divine's "divine economic socialism" teachings, and infused with Jones's personal communist worldview. Jones referred to his views as "Apostolic

Apostolic may refer to:

The Apostles

An Apostle meaning one sent on a mission:

*The Twelve Apostles of Jesus, or something related to them, such as the Church of the Holy Apostles

*Apostolic succession, the doctrine connecting the Christian Churc ...

Socialism". Jones concealed the communist aspects of his teachings until the late 1960s, following the relocation of Peoples Temple to California, where he began to gradually introduce his full beliefs to his followers.

Jones taught that "those who remained drugged with the opiate of religion had to be brought to enlightenment", which he defined as socialism. Jones asserted that traditional Christianity had an incorrect view of God. By the early 1970s, Jones began deriding traditional Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

as "fly away religion", rejecting the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

as being a tool to oppress women and non-whites. Jones referred to traditional Christianity's view of God as a " Sky God" who was "no God at all". Instead, Jones claimed to be God, and no God beside him.

Jones increasingly promoted the idea of his own divinity, going so far as to tell his congregation that "I am come as God Socialist." Jones carefully avoided claiming divinity outside of Peoples Temple, but he expected to be acknowledged as god-like among his followers. Former Temple member Hue Fortson Jr. quoted him as saying:

What you need to believe in is what you can see.... If you see me as your friend, I'll be your friend. As you see me as your father, I'll be your father, for those of you that don't have a father.... If you see me as your savior, I'll be your savior. If you see me as your God, I'll be your God.Further attacking traditional Christianity, Jones authored and circulated a tract entitled "The Letter Killeth", criticizing the

King James Bible

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

, and dismissing King James as a slave owner and a capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

who was responsible for the corrupt translation of scripture. Jones claimed he was sent to share the true meaning of the gospel which had been hidden by corrupt leaders.

Jones rejected even the few required tenets of the Disciples of Christ denomination. Instead of implementing the sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the real ...

as prescribed by the Disciples, Jones followed Father Divine's holy communion

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

practices. Jones created his own baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

al formula, baptizing his converts "in the holy name of Socialism".

Explaining the nature of sin, Jones stated, "If you're born in capitalist America, racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

America, fascist America, then you're born in sin. But if you're born in socialism, you're not born in sin." Drawing on a prophecy in the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of R ...

, he taught that American capitalist culture was irredeemable "Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

".

Jones frequently warned his followers of an imminent apocalyptic nuclear race war. He claimed that Nazis and white supremacists would put people of color into concentration camps. Jones said he was a messiah sent to save people. He taught his followers the only way to escape the supposed imminent catastrophe was to accept his teachings, and that after the apocalypse was over, they would emerge to establish a perfect communist society.

Publicly, Jones took care to always couch his socialist views in religious terms, such as "apostolic social justice". "Living the Acts of the Apostles" was his euphemism for living a communal lifestyle. While in the United States, Jones feared the public discovering the full extent of his communist views, which he worried would cost him the support of political leaders and risk Peoples Temple being ejected from the Disciples of Christ. Jones feared losing the church's tax-exempt status and having to report his financial dealings to the Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting U.S. federal taxes and administering the Internal Revenue Code, the main body of the federal statutory ta ...

.

Historians are divided over whether Jones actually believed his own teachings, or was just using them to manipulate people. Jeff Guinn said, "It is impossible to know whether Jones gradually came to think he was God's earthly vessel, or whether he came to that convenient conclusion to enhance his authority over his followers." In a 1976 interview, Jones claimed to be an agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient ...

and/or an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

. Marceline admitted in a 1977 ''New York Times'' interview that Jones was trying to promote Marxism in the U.S. by mobilizing people through religion. She said Jones called the Bible a "paper idol" that he wanted to destroy.

Jones taught his followers that the ends justify the means and authorized them to achieve his vision by any means necessary. Outsiders would later point to this aspect of Jones's teachings to allege that he did not genuinely believe in his own teachings, but was "morally bankrupt" and only manipulating religion and other elements of society "to achieve his own selfish ends".

Early reports of abuse

Jones began using illicit drugs after moving to California, which further heightened his paranoia. He increasingly used fear to control and manipulate his followers. Jones frequently warned his followers that there was an enemy seeking to destroy them. The identity of that enemy changed over time from the Ku Klux Klan, to Nazis, to redneck vigilantes, and finally the American government. He frequently prophesied that fires, car accidents, and death or injury would come upon anyone unfaithful to him and his teachings. He constantly pressed his followers to be aggressive in promoting and fulfilling his beliefs. Jones established a Planning Commission made up of his lieutenants to direct the Peoples Temples' communal lifestyle. Jones, through the Planning Commission, began controlling all aspects of the lives of his followers. Members who joined Peoples Temple turned over all their assets to the church in exchange for free room and board. Members who worked outside of the Temple turned over their income to be used for the benefit of the community. Jones directed groups of his followers to work on various projects for additional income and set up an agricultural operation inRedwood Valley

Redwood Valley (formerly Basil) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Mendocino County, California, United States. It is located north of Ukiah, the county seat, at an elevation of , and comprises the northern portion of the Ukiah Valley. It i ...

to grow food. Large community outreach projects were organized, and Temple members were bussed to perform work and community service across the region.

The first known cases of serious abuse in Peoples Temple arose in California as the Planning Commission carried out discipline against members who were not fulfilling Jones's vision or following the rules. Jones's control over the members of Peoples Temple extended to their sex lives and who could be married. Some members were coerced to get abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

s. Jones began to require sexual favors from the wives of some members of the church, and raped several male members of his congregation.

Members who rebelled against Jones's control were punished with reduced food rations, harsher work schedules, public ridicule and humiliations, and sometimes with physical violence. As the Temple's membership grew, Jones created an armed security group to ensure order among his followers and to guarantee his own personal safety.

Focus on San Francisco

By the end of 1969, Peoples Temple was growing rapidly. Jones's message of economic socialism and racial equality, along with the integrated nature of Peoples Temple, proved attractive, especially to students and racial minorities. By 1970, the Temple opened branches in several cities includingSan Fernando

San Fernando may refer to:

People

*Ferdinand III of Castile (c. 1200–1252), called ''San Fernando'' (Spanish) or ''Saint Ferdinand'', King of Castile, León, and Galicia

Places Argentina

*San Fernando de la Buena Vista, city of Greater Buenos ...

, San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, and Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

as Jones began shifting his focus to major cities across California because of limited expansion opportunities in Ukiah. He eventually moved the Temple's headquarters to San Francisco, which was a major center for radical protest movements. By 1973, Peoples Temple reached 2,570 members, with 36,000 subscribers to its fundraising newsletter.

Jones grew the Temple by purposefully targeting other churches. In 1970, Jones and 150 of his followers took a trip to San Francisco's Missionary Baptist Church. Jones held a faith healing revival meeting wherein he impressed the crowd by claiming to heal a man of cancer; his followers later admitted to helping him stage the "healing". At the end of the event, he began attacking and condemning Baptist teachings and encouraging the members to abandon their church and join him.

The event was successful, and Jones recruited about 200 new members for Peoples Temple. In a less successful attempt in 1971, Jones and a large number of his followers visited the tomb and shrine erected for Father Divine shortly after his death. Jones confronted Divine's wife and claimed to be the reincarnation of Father Divine. At a banquet that evening, Jones's followers seized control of the event and Jones addressed Divine's followers, again claiming that he was Father Divine's successor. Divine's wife rose up and accused Jones of being the devil in disguise and demanded he leave. Jones managed to recruit only twelve followers through the event.

Jones became active in San Francisco politics and was able to gain contact with prominent local and state politicians. Thanks to their growing numbers, Jones and Peoples Temple played an instrumental role in George Moscone

George Richard Moscone (; November 24, 1929 – November 27, 1978) was an American attorney and Democratic politician. He was the 37th mayor of San Francisco, California from January 1976 until his assassination in November 1978. He was known ...

's election as mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

in 1975. Moscone subsequently appointed Jones as the chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission.

Jones hosted local political figures at his San Francisco apartment for discussions. In September 1976, Assemblyman Willie Brown served as master of ceremonies at a large testimonial dinner for Jones attended by Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Jerry Brown

Edmund Gerald Brown Jr. (born April 7, 1938) is an American lawyer, author, and politician who served as the 34th and 39th governor of California from 1975 to 1983 and 2011 to 2019. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected Secretary of S ...

and Lieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

Mervyn Dymally

Mervyn Malcolm Dymally (May 12, 1926 – October 7, 2012) was an American politician from California. He served in the California State Assembly (1963–66) and the California State Senate (1967–75) as the 41st Lieutenant Governor of Californi ...

. At that dinner, Willie Brown touted Jones as "what you should see every day when you look in the mirror" and said he was a combination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American political activist, philosopher, academic, scholar, and author. She is a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. A feminist and a Marxist, Davis was a longtime member of ...

, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, and Mao. Harvey Milk

Harvey Bernard Milk (May 22, 1930 – November 27, 1978) was an American politician and the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Milk was born and raised in N ...

spoke to audiences during political rallies held at the Temple, and he wrote to Jones after one such visit:

Rev Jim, It may take me many a day to come back down from the high that I reach today. I found something dear today. I found a sense of being that makes up for all the hours and energy placed in a fight. I found what you wanted me to find. I shall be back. For I can never leave.Through his connections with California politicians, Jones was able to establish contacts with key national political figures. Jones and Moscone met privately with vice presidential candidate

Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928 – April 19, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 42nd vice president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. A U.S. senator from Minnesota ...

on his campaign plane days before the 1976 election, leading Mondale to publicly praise the Temple.

First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

Rosalynn Carter

Eleanor Rosalynn Carter ( ; née Smith; born August 18, 1927) is an American writer and activist who served as First Lady of the United States from 1977 to 1981 as the wife of President Jimmy Carter. For decades, she has been a leading advocate ...

met with Jones on multiple occasions, corresponded with him about Cuba, and spoke with him at the grand opening of the San Francisco headquarters—where he received louder applause than she did. Jones forged alliances with key columnists and others at the ''San Francisco Chronicle

The ''San Francisco Chronicle'' is a newspaper serving primarily the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California. It was founded in 1865 as ''The Daily Dramatic Chronicle'' by teenage brothers Charles de Young and M. H. de Young, Michael H. de ...

'' and other press outlets that gave Jones favorable press during his early years in California.

Jonestown

Publicity problems

Jones began to receive negative press beginning in October 1971 when reporters covered one of Jones's divine healing services during a visit to his old church in Indianapolis. The news report led to an investigation by the Indiana State Psychology Board into Jones's healing practices in 1972. A doctor involved in the investigation accused Jones of "quackery" and challenged Jones to give tissue samples of the material he claimed fell off people when they were healed of cancer. The investigation caused alarm within the Temple. Jones had been performing faith healing "miracles" since his joint campaigns with William Branham. "On several occasions his healings were revealed as nothing but a hoax." In one incident, Jones drugged Temple member Irene Mason, and while she was unconscious, a cast was put on her arm. When she regained consciousness, she was told she had fallen and broken her arm and taken to the hospital. In a subsequent healing service, Jones removed her cast off in front of the congregation and told them she was healed. In other instances, Jones had someone from his inner circle enter the prayer line for healing of cancer. After being "healed" the person would pretend to cough up their tumor, which was actually a chickengizzard

The gizzard, also referred to as the ventriculus, gastric mill, and gigerium, is an organ found in the digestive tract of some animals, including archosaurs (pterosaurs, crocodiles, alligators, dinosaurs, birds), earthworms, some gastropods, so ...

.

Jones also pretended to have "special revelations" about individuals which revealed supposed hidden details of their lives.

Jones was fearful that his methods would be exposed by the investigation. In response, Jones announced he was terminating his ministry in Indiana because it was too far from California for him to attend to and downplayed his healing claims to the authorities. The issue only escalated however, and Lester Kinsolving ran a series of articles targeting Jones and Peoples Temple in the ''San Francisco Examiner

The ''San Francisco Examiner'' is a newspaper distributed in and around San Francisco, California, and published since 1863.

Once self-dubbed the "Monarch of the Dailies" by then-owner William Randolph Hearst, and flagship of the Hearst Corporat ...

'' in September 1972. The stories reported on Jones's claims of divinity and exposed purported miracles as a hoax.

In 1973, Ross Case, a former follower of Jones, began working with a group in Ukiah to investigate Peoples Temple. They uncovered a staged healing, the abusive treatment of a woman in the church, and evidence that Jones raped a male member of his congregation. Reports of Case's activity reached Jones, who became increasingly paranoid that the authorities were after him. Case reported his findings to the local police, but they took no action.

Shortly after, eight members of Peoples Temple made accusations of abuse against the Planning Commission and Peoples Temple staff members. They accused members of Planning Commission of being homosexuals and questioned their true commitment to socialism, before leaving the Peoples Temple. Jones became convinced he was losing control and needed to relocate Peoples Temple to escape the mounting threats and allegations.

On December 13, 1973, Jones was arrested and charged with lewd conduct for allegedly masturbating

Masturbation is the sexual stimulation of one's own genitals for sexual arousal or other sexual pleasure, usually to the point of orgasm. The stimulation may involve hands, fingers, everyday objects, sex toys such as vibrators, or combinati ...

in the presence of a male undercover

To go "undercover" (that is, to go on an undercover operation) is to avoid detection by the object of one's observation, and especially to disguise one's own identity (or use an assumed identity) for the purposes of gaining the trust of an indi ...

LAPD

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), officially known as the City of Los Angeles Police Department, is the municipal police department of Los Angeles, California. With 9,974 police officers and 3,000 civilian staff, it is the third-large ...

vice officer in a movie theater restroom near Los Angeles's MacArthur Park

MacArthur Park (originally Westlake Park) is a park dating back to the late 19th century in the Westlake, Los Angeles, Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles. In the early 1940s, it was renamed after General Douglas MacArthur, and later designated ...

. On December 20, 1973, the charge against Jones was dismissed, though the details of the dismissal are not clear. The court file was sealed, and the judge ordered that records of the arrest be destroyed.

Formation

In the fall of 1973, Jones and the Planning Commission devised a plan to escape from the United States in the event of a government raid, and they began to develop a longer-term plan to relocate Peoples Temple. The group decided on Guyana as a favorable location, citing its recent revolution, socialist government, and the favorable reaction Jones received when he traveled there in 1963. In October, the group voted unanimously to set up an agricultural commune in Guyana. In December, Jones and Ijames traveled to Guyana to find a suitable location. In a newspaper interview, Jones indicated that he would rather settle his commune in a communist country like China or theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, and was saddened about his inability to do so. Jones described Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

and Stalin as his heroes, and saw the Soviet Union as an ideal society.

By the summer of 1974, land and supplies were purchased in Guyana. Ijames was put in charge of the project and oversaw the installation of a power generation station, clearance of fields for farming, and the construction of dormitories to prepare for the first settlers. In December 1974, the first group arrived in Guyana to start operating the commune that would become known as Jonestown.